Why I forgot your name – a lesson on spaced repetition for training

Published

May 7, 2020

Author

Share

According to Marcus Cicero, the great Roman orator, ‘Memory is the treasury and guardian of all things.’ Said never to forget a name, Cicero was famous for utilizing the ‘loci’ method of linking and recalling knowledge, which involved repeatedly visiting a ‘memory palace’ in his mind.

The chances are, between back-to-back meetings and your overflowing inbox, you probably haven’t got around to creating your own ‘memory palace’ to store and revise every newly acquired piece of knowledge or name collected. Most likely, you’ll relate to the excruciatingly awkward social situation of forgetting a colleague’s name and not being able to introduce them at Friday night drinks. It happens to the best of us. Or, most of us…

How the brain processes memory and retention

In neuroscientists’ speak, such socially awkward gaffes are incredibly common ‘retrieval failures’ within our brain hardware. Names are prime targets for falling off the short-term memory cliff, never to be seen again. Forgetting a name is not a sign of an intellectual deficit; it is because transferring information from short to long-term memory is no easy task. We need to trick the brain into thinking that the new knowledge acquired matters, and what you think is important, and what your brain categorises as important can be entirely different.

Despite genuinely engaging with a new colleague, our brain might still fail to register a name; this is because names are essentially arbitrary pieces of information, and thus, not deemed important enough to file away for future use. The same principle can be applied to phone numbers. Once upon a time, before the advent of smartphones, most people carried around a memorized catalog of essential contact numbers in their heads. Not so anymore. Why? We have acclimatized to digital devices doing the remembering for us. Unfortunately, the same neural wiring challenges occur when it comes to corporate training and learning.

Contemplating how we learn is the first step in improving professional learning outcomes. An awareness of how human memory systems operate enables us to create workarounds and essentially hack our brain hardware.

To be fully aware of what we are up against in terms of the potential deterioration of new skills and knowledge, it is worthwhile revisiting the work of the nineteenth-century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. Famous for conceptualizing the ‘Forgetting Curve,’ Ebbinghaus found that when learning content that is delivered in a stand-alone block, without any follow-up, it will be almost entirely lost within 90 days. The deterioration curve is scarily steep:

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Spaced repetition

So how do we avoid sending critical learnings to the brain dumpster? Spaced repetition. It’s important to note that endless repetition alone won’t deliver the results we are after; it’s only when information is revised over successively longer time intervals that the magic happens. Over a hundred years ago, Ebbinghaus recognised the fact that ‘with any considerable number of repetitions a suitable distribution of them over a space of time is decidedly more advantageous than the massing of them at a single time.’ It is HIIT (high-intensity interval training) for the brain. By using interval repetitions to re-expose the brain to information, memories are actively reconstructed.

Spaced repetition acknowledges the fact that consolidating information in our long term memories takes time. Think of spaced repetition as the antithesis to cramming the night before an exam. It turns out there is a scientific reason for teachers and parents perennially pleading students not to leave studying for the test to the last minute. In a very real sense, insulating neural connections does not happen overnight. It is only through staggered repetition that the myelin coating of the axon sheath (memory insulation) can consolidate. In non-neuroscience terms, by revising information just as memories are starting to decay, and doing this repeatedly at increasingly spaced intervals, learnings become ‘sticky,’ resulting in longer-term retention. Spaced repetition strategically bounces between forgetting and remembering.

The theoretical underpinning of spaced repetition is not new. In 1932, British psychologist C. A. Mace expanded on Ebbinghaus’s theory, suggesting that revision of learning material over 1, 2, 4 and 8-day intervals would result in deeper semantic processing, making memories more durable. Studies into expanded rather than uniform spacing intervals became more sophisticated from the 1970s onwards.

At the most basic level, before incorporating more sophisticated scheduling algorithms (like Brain Boost spaced repetition app), numerous peer-reviewed studies have corroborated the huge wins spaced repetition provides learners— in academic and corporate learning settings.

Let’s compare our student cramming the night before the exam to an ‘ideal’ scenario in which the learner uses spaced repetition strategies. A 2007 study that compared exam results between crammers and spaced revealed that when students were examined one year after the last review of the material, the spaced revisers performed 77 per cent better than the crammers. If students were examined after the first seventy days, the results were even starker, with the progressive revisers outperforming the crammers by 111 per cent.

Spaced Repetition SRS

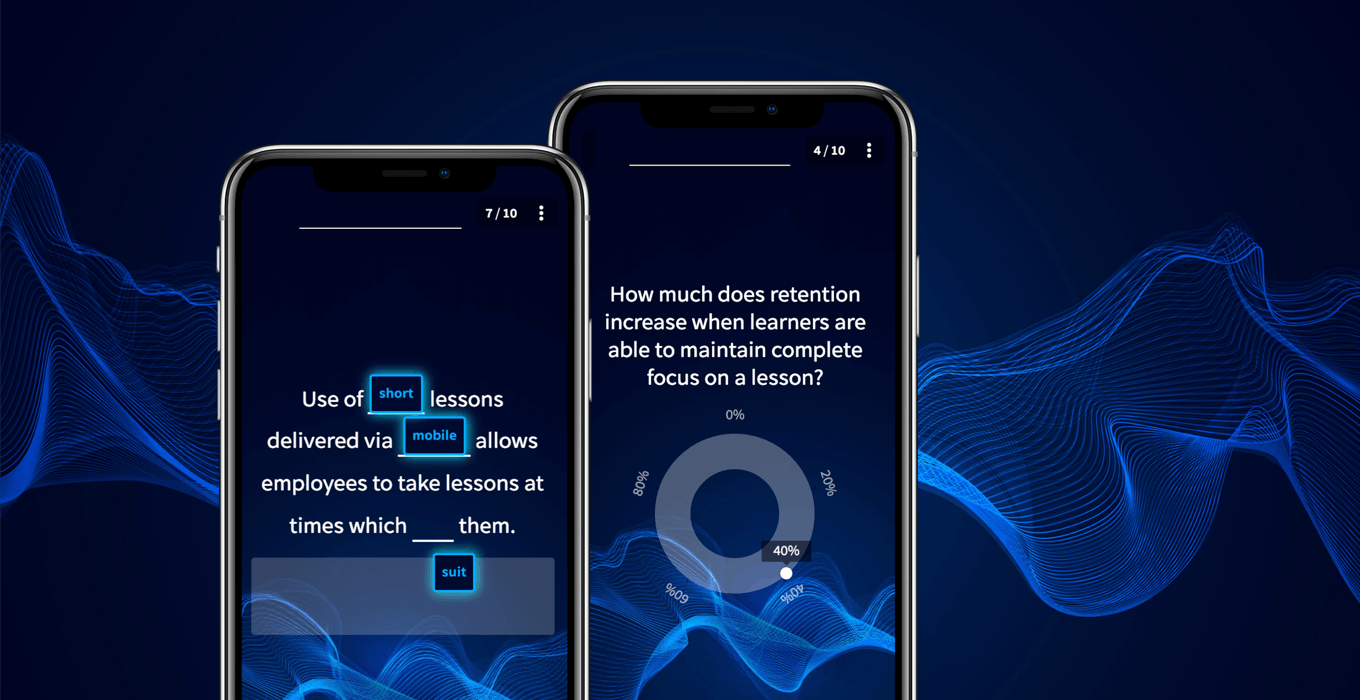

What does spaced repetition mean in practice for training opportunities? With microlearning apps such as SC Training (formerly EdApp) embracing SRS (Spaced Repetition Software), corporate learning trajectories have been flipped, with companies benefiting from the overwhelmingly positive returns on training investments. SC Training (formerly EdApp)’s incorporation of the SuperMemo (SM-2) scheduling algorithm is the brain hack we have all been searching for to boost long-term retention. By strategically targeting ideal intervals between revising, capturing items of knowledge just as they are starting to deteriorate, learners in the corporate space create their own ‘memory palaces’ with the aid of AI, without needing to be a Cicero.

Spaced repetition teaches the brain that reappearing content is worth filing away in the long-term memory bank; it triggers the brain to register, ‘this is important because I might need to access it again in the future.’ By significantly boosting long-term retention, spaced repetition arguably tackles the biggest pain point in corporate training—hours and hours of lost learning. While capitalising on spaced repetition technology is undoubtedly high ROI, it may not, however, guarantee that you’ll remember that colleague’s name at the next Christmas party…

Sources:

1. See Hermann Ebbinghaus (1913). Memory; a contribution to experimental psychology. New York City: Teachers college, Columbia University.

2. Ibid. p.89.

3. C. A. Mace (1932) The Psychology of Study. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

4. See T. K. Landauer & R. A. Bjork (1978). ‘Optimum rehearsal patterns and name learning.’ In M. M. Gruneberg, P. E. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.),(pp. 625-632). London: Academic Press.

5. See Doug Rohrer & Harold Pashler (2007). ‘Increasing Retention Without Increasing Study Time.’ Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 183–186.

6. Eric Jaffe (November 2008) ‘Will That Be on the Test?’ In APS Observer 21:10.

Author